Robert S. Edwards Papers

-

Please use the Collection Organization below to place requests

Scope and Contents

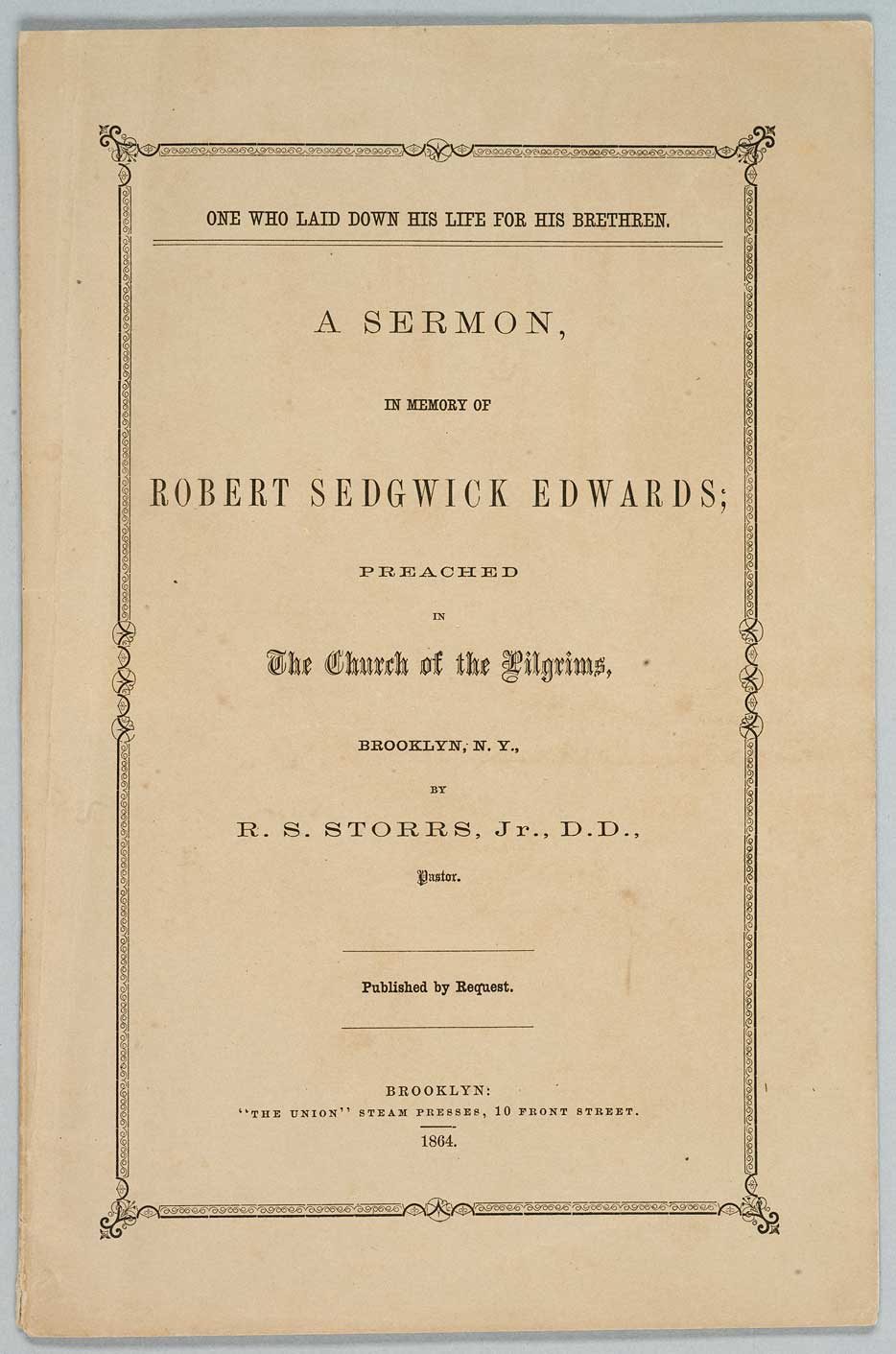

The Edwards papers include 60 manuscript items, all with a bearing on the Civil War service of Robert Sedgwick Edwards. About 20 per cent of these items postdate Edwards's death. Forty-five of the manuscripts are personal letters, authored during the war. Fourteen were written by Robert Edwards himself: five to relatives in Andover and Brooklyn, and nine to friends in Philadelphia. Of the 28 letters written by Robert's older brother, Ogden Ellery Edwards, Jr. (b. 1829), and by Ogden's wife Helen E. Edwards (known as Nellie), twenty-two are addressed to Robert; there is also one written to Annie, and five to another sister, Frances (Fanny) Edwards Rogers. The remaining letters include one addressed to William W. Edwards by Cpl. Dayton Britton of Co. C, 48th New York, describing Robert's death, and two more addressed to Annie by Edward D. Edwards, a cousin, and Rev. William Allen, a family friend from Northampton, Massachusetts. The collection also contains three maps, all sketched by Robert but undated, showing 1) the 48th New York's maneuvers at Port Royal Ferry; 2) the layout of the regiment's camp at an unspecified location; and 3) a plan of Fort Pulaski. The papers also include several printed items, including a copy of Rev. Storrs's funeral sermon, published in 1864. There are also several pieces of realia, including a 5 x 9 cm. fragment of the surrender flag flown over Fort Pulaski in April 1862, which Robert mailed to a relative in Brooklyn. The presence in the collection of several manuscript notes of later nineteenth-century origin, written in two unidentified hands, suggests that the papers were purposely gathered and preserved to commemorate Robert's death, most likely by family members. Ogden's and Nellie's letters typically fill the four pages of a single folded sheet, while Robert's tend to be considerably longer, filling sometimes six, eight, and even ten pages of multiple sheets, and often taking advantage of all available space in the folds and margins. Robert Edwards's letters—addressed to his sister Annie, his aunt Helen, his cousin Mary, and to friends in Philadelphia identified only as "Charley" and "Miss Leavitt" (the former possibly Charles W. Leavitt, who served in Pennsylvania emergency regiments called up during the 1862 Maryland and 1863 Gettysburg campaigns)—reveal a generally sober and practical cast of mind. Though he was confident in the eventual success of Union arms, he harbored no illusions of a quick or bloodless victory. He fully expected that the war would require heavy sacrifices, and in the letters he often faults Union military commanders for their lack of aggressiveness. Just two weeks after Shiloh (6-7 April 1862), up to that point the bloodiest battle of the war, Robert complains to Charley that "Those Western Chaps seem to be getting all the glory of the day. They have done some terrible fighting. Here it is hard to realize all this, Everything is done on the plan of 'nobody hurt'" (20 April 1862). He is especially critical of McClellan, whose poor performance during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign comes in for pointed scrutiny in Robert's letter of 3 September 1862. In contrast, Ogden defends the general, arguing that meddling politicians brought about the disaster on the Peninsula. Ogden's impulse to support McClellan may be partially explained by his apparent connections with the Democratic Party; he informs Robert in the same letter that if the Democrats return to power, he may be able to exploit connections in New York to get Robert into the regular army. Ogden's and Nellie's letters to Robert contain much family and social news. The couple's infant daughter, Catherine Shepherd Edwards (born in Manila on 24 May 1862), regularly features, as do the family's domestic arrangements and their wartime reading habits. Nellie writes on 22 November 1861 of putting down Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in favor of contemporary essays and war correspondence from Atlantic, Harper's Weekly, Vanity Fair, and Littel's Living Age: "It is indeed impossible to interest ourselves in the records of dead and buried ages, when (as is so often said) we are every day now living History so rapidly." A number of the letters discuss life in the aftermath of the earthquake that struck Manila in 1863. In his 1 March 1864 letter to Annie, Ned writes that "Manila is a very different place from what it was before the Terremoto": the pulling down & putting up buildings has of course, caused a vast amount of rubish, lime, stones bricks &c &c—to accumalate—all this stuff the Govt have been having carted off & put on all the streets & roads about Manila – So we have the full benefit of Lime dust & one is really stiffled in driving about. The letters from the Philippines are also filled with commentary on the mercantile trade, international politics, and especially the progress of the war. Because mail from the United States often took six weeks or more to reach them in Manila, both Ogden and Nellie constantly sought news of the fighting from all quarters. "It is over five weeks now since the last [mail] was received," Nellie writes on 23 January 1862, "and we are inexpressibly thirsty for 'news.'" Almost all the Americans living in Manila during the war came from the Northeast, and were thus naturally inclined to support the Union cause. But they also followed developments at home with keen interest because their fortunes in trade were closely tied with Union fortunes on the battlefield; as Ogden himself puts it on 11 January 1862, "Our business for the coming year will much depend upon the course of affairs at home." Generally speaking, the war seems to have had a positive effect on business for Ogden's firm. In a 29 June 1862 letter to Robert, he comments on the increased wartime demand for indigo, used in the manufacture of blue dye for Federal uniforms: You ask about Indigo & if the increased demand has not helped us – Yes we cleared about $4000# on a lot which arrived at the right time – Business has been very good the past 6. mos at least $5pm clear & I think that we shall get about $50.000# for the years work – If so we shall be again in comfortable circumstances – All our earnings since 1856 have gone to make up what was lost during the 15 mos of my absence from Manila but I think affairs are likely to go straight for the future. Robert's last letters were written from Morris Island from 11 to 17 July 1863, the day before his death. They describe combat operations leading up to the 18 July attack. On 10 July 1863, Strong's brigade, including four companies from the 48th New York, landed on the southern tip of Morris Island. Robert's 11 July and 13 July letters describe this landing, which was accomplished under fire as the brigade's flotilla of open boats came within range of Confederate shore batteries. They succeeded in breaking the Confederate defenses and pushed to within 600 yards of Fort Wagner (see Official Records, Series 1, Vol. 28, Part I, p. 12) before it was determined that the fort was too strong to be carried. The 48th New York lost 25 men killed or wounded in this action. An attempt to take the fort by direct assault was made the next day by other elements of the Union expeditionary force, but this was thrown back with heavy losses. Siege operations began in earnest on 12 July, as work commenced on a number of concealed batteries and, further forward, a series of parallel infantry trenches dug to within 700 yards of Wagner's ramparts. Robert's letter to Annie of 16-17 July was written just after his company had returned to camp from a 48-hour stretch in the trenches—"the rifle pits," he writes, "are each merely a trench about six feet wide and two and a half deep, the earth thrown up in front so as to form an embankment covering the men breast high"—where they had to contend with intense heat and blowing sand, as well as sniper fire and an occasionally well-placed shell: "several shells burst so close to us as to make the air sulphurous and one covered me with sand at the bottom of my pit." The Confederates made a probing attack on these advanced lines during the early morning hours of 14 July, but it was repulsed after some close range and even hand-to-hand fighting that Robert describes in detail (Britton's letter also describes this action, noting Robert's coolness under fire). Though duty on the front lines was grueling and dangerous, Morris Island did afford some relief to troops rotating to reserve areas. "Our great luxury here is bathing," Robert writes from the abandoned Confederate camp his regiment occupied; "the beach is a fine one and we frequently take a dip both morning and evening." Rev. Storrs's funeral sermon contains an extract from an unsent letter, recovered with Robert's personal baggage, that he was writing to Annie on the morning of 18 July. In it, Robert reaffirms his commitment to the cause for which he was fighting. "I am satisfied," he writes, "that I shall never find a better use for my life, than to give it up in this War." This he did at the head of his company during that evening's action. The 48th New York struck the fort's southeast salient and sea-face, which they briefly occupied before mounting casualties, some inflicted by the fire of supporting Union regiments, forced the survivors to withdraw. Robert fell after having reached the fort's rampart, where intense fighting raged for more than an hour. Two separate accounts of his death are included in the collection. The first is an excerpt from a 20 August 1863 letter of William W. Edwards to his wife, copied in an unidentified hand. The letter conveys particulars of Robert's death gathered from members of the 48th New York who had been detailed to Brooklyn on recruiting service. The second is Britton's letter to William W. Edwards, written from Hilton Head, South Carolina on 1 January 1864. Not surprisingly, given that both are addressed to grieving family members, the accounts emphasize the heroic nature of Robert's death, indicating that he gained Wagner's parapet and took up the fallen national flag after the regiment's color sergeant was wounded. According to the Edwards excerpt, Robert was shot in the chest after scaling the parapet, and immediately toppled back into the flooded ditch. Britton, a corporal in Robert's company, wrote some five months after the battle to request a copy of Storrs's sermon and to provide Robert's uncle with "a simple & truthful account of all facts connected with the death of your late Nephew." He reports that during the attack he saw Robert's body lying near the top of the rampart, head-down on the slope, with his left side torn away (probably by a canister round). A moment earlier he had seen "Lieut Edwards rushing up the slope of the fort near the parapet, wavering the glorious Stars and Stripes over his head—speaking out in a cool & determined tone—'Come on Company C—follow this Flag—the Fort must be ours.'" Britton's letter attests to the esteem in which Robert was held by his comrades, who to a man "complimented Your Nephew, and all felt that he was 'every inch a Soldier.'" It also bitterly laments the folly of the 18 July attack, which revealed that Fort Wagner's armaments and large garrison of veteran troops, protected by sand and palmetto-log embankments, had survived the massive pre-assault bombardment nearly unscathed. "We were truly decoyed into that slaughter house," Britton writes; "The rebels held out the bate—and we eagerly seized it." The fort finally fell to Union siege forces on 7 September 1863.

Dates

- Creation: 1861-1865

Creator

- Edwards, Robert S. (Robert Sedgwick), 1838-1863 (Person)

- Edwards, Ogden Ellery, Jr., 1829- (Person)

- Edwards, Helen E. (Person)

Conditions Governing Access

There are no access restrictions on this collection.

Conditions Governing Use

Copyright status for collection materials is unknown. Transmission or reproduction of materials protected by U.S. Copyright Law (Title 17, U.S.C.) beyond that allowed by fair use requires the written permission of the copyright owners. Works not in the public domain cannot be commercially exploited without permission of the copyright owners. Responsibility for any use rests exclusively with the user.

Biographical / Historical

Robert Sedgwick Edwards, son of Ogden Ellery Edwards (1802-1848) and Catherine Shepherd Edwards (1806-1843), was born in New York City on 3 January 1838. After his father's death in 1848, he went to live in Brooklyn with his grandparents, William (1770-1851) and Rebecca Tappan Edwards (1775-1857). William Edwards, a grandson of the Congregational minister and theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758), introduced substantial improvements in the manufacture of leather, and amassed significant wealth from the tanning business he established along the Schoharie River at Hunter, Greene County, New York. Edwards retired to Brooklyn in 1834, but the family retained strong connections to Hunter and the Catskills region. The 1850 Federal census identifies the 11-year-old Robert as a resident in his grandparents' household, which they also shared with two adult sons, Henry (1798-1885) and Amory Edwards (1814-1881), both merchants. The census also indicates that in 1850 Robert's sister Anna Louisa Edwards (b. 1839), known as "Annie," was living next door at the home of an uncle, Henry Rowland, a flour merchant. Robert remained in Brooklyn and New York City for most of the following decade, although neither he nor his younger sister is listed in the 1860 Federal census as a resident of either city. According to the published version of a sermon preached by the Rev. Richard S. Storrs at his funeral, Robert became a member of Brooklyn's Church of the Pilgrims in 1854, and soon began teaching Sunday school at the Warren Street Mission School. Storrs indicates that except for a two-year interval in Philadelphia, Robert remained at the school until the fall of 1861. For at least part of this time, he was employed by the import and commercial goods firm of Richards, Haight, & Co. in New York City. From fall 1861 to summer 1863, it appears that Annie Edwards stayed with relatives in Andover, Massachusetts. She had returned to Brooklyn by the fall of 1863 to live with her uncle, William W. Edwards (1796-1876), an officer at the Dime Savings Bank, and his wife Helen Mann Edwards (1800-1887). Robert Edwards enlisted on 1 August 1861 in the "Continental Guard," a volunteer regiment subsequently designated the 48th New York Infantry. A document in the collection dated 2 August 1861 and signed by the Continental Guard's colonel, Rev. James H. Perry, and acting adjutant (later regimental quartermaster) Irving M. Avery, describes Edwards as a lieutenant and authorizes him to recruit men for the regiment. Edwards was formally commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant in the 48th New York's Company D on 21 August 1861, and soon after transferred to Co. E. On 15 April 1862, upon his promotion to 1st lieutenant, Edwards was transferred from Co. E to Co. C. He was officially commissioned 1st lieutenant on 29 April. He was killed on 18 July 1863 on Morris Island in the failed Union assault on Fort Wagner, a strongpoint in the network of Confederate fortifications guarding the approaches to Charleston Harbor. The "Continental Guard" was organized at "Camp Wyman," Fort Hamilton, New York. The regiment was officially numbered and recognized as the 48th New York Infantry on 14 September 1861, and its ten companies were mustered in to Federal service between 16 August and 10 September 1861. The 48th New York was recruited principally from the urban middle classes in Brooklyn, though it also drew volunteers from New York City, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. The regiment was known as "Perry's Saints," in honor of Col. Perry, a West Point graduate and prominent Brooklyn minister, and it seems that Perry's reputation attracted to the regiment a comparatively high number of deeply religious, highly educated enlistees. According to Nichols's regimental history, New York governor Edwin Morgan permitted Col. Perry to bypass state regulations so that he could hand-select his own officers, among whom were at least three ordained ministers (see Nichols, pp. 25-7; Palmer, p. 12). On 17 September 1861, the regiment departed New York for Washington DC, where it was attached to the 1st Brigade, South Carolina Expeditionary Corps, under Maj. Gen. Thomas W. Sherman. With this corps, the 48th New York participated on 1 January 1862 in the capture of Port Royal Ferry. From late January to April 1862, the regiment was engaged in siege operations against Fort Pulaski, guarding the river entrance to Savannah, Georgia. The 48th remained at Pulaski after the fort was reduced by bombardment on 11 April, performing garrison duty there until June 1863. On 18 June, the regiment, minus two companies, was dispatched to the coastal islands opposite Charleston, South Carolina, where it was attached to Brig. Gen. George C. Strong's 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, X Corps, Department of the South. On 10 July 1863, Strong's brigade (now designated 1st Brigade, U.S. Forces, Morris Island) landed at the southern tip of Morris Island and overran the advanced Confederate lines below Fort Wagner. Assigned a supporting role in the 18 July assault on the fort itself, the 48th suffered heavy casualties, losing a total of 242 men killed, wounded, and missing (see New York in the War of the Rebellion, p. 2357). Ogden and Nellie Edwards were living in the Philippines during the war, where Ogden was employed by the American shipping firm of Peele, Hubbell, & Co., exporters of abaca (hemp), sugar, and indigo. They were members of a very small community—approximately 200 by 1869—of American, British, and non-Spanish European merchants in Manila in the 1860s (see Owen, "Americans in the Abaca Trade," p. 202). Edwards had arrived in Manila in 1852, and was admitted as a nonproprietary junior partner in the firm on 1 January 1855. He was absent from Manila for fifteen months spanning 1856-57, during which time he and Nellie were married. From 1855 on he and two other junior partners, Horatio N. Palmer and Richard D. Tucker, managed the company's business operations. They purchased the firm outright in 1859, upon the death of the owner, William P. Pierce. Ogden's cousin Edward D. Edwards (1841-1868), a son of William W. Edwards, also lived in Manila during the war. Edward, known as "Ned," arrived in Manila during the winter of 1860-61, according to Robert's letter of 6 March 1862, and was employed by Ogden's firm as a clerk and bookkeeper until declining health forced his departure in 1866. Robert took to military life very quickly. "Thus far I have Enjoyed soldier life to the finger tips," he writes on 25 September 1861 from Washington, D.C.'s "Camp Sherman." Six months later on Daufuskie Island (2 March 1862), long after the "charm of novelty" of camp life had worn off, he assures Charley that he "would not be hired to leave the service before this business is thoroughly settled." His first experience under fire was at Port Royal Ferry, South Carolina on 1 January 1862. The 47th and 48th New York regiments, temporarily attached to Brig. Gen. Isaac I. Stevens's Port Royal Expeditionary Force, were deployed on the Union right flank in support of the attack on the fortifications at the ferry. During their advance, they came upon a Confederate battery concealed in a strip of woods, supported by infantry and protected from frontal attack by a marsh. As Union skirmishers sought a route to take the battery by the left flank, the main body of the regiment was deployed in line of battle and came under a largely ineffectual, long-range rifle fire. The regiment had just resumed the advance when word came to disengage, as the fortifications at the ferry had been taken. Edwards describes the engagement twice, with slight variation in the details, in a 6 January letter to his cousin Mary Elizabeth Edwards, and a 20 January letter to Charley. He writes that the advanced units in the attack, seen from a distance, looked like "a broad black ribbon with a glittering fringe" (20 January 1862). Soon the balls came "whizzing over our heads and occasionally one would strike the ground in front and scatter dirt over us" (6 April). The letters reflect the sensations of disorder typically experienced by Civil War combatants, on fields where maneuver and visibility was limited by vegetation, smoke, and irregularities in terrain. Robert reports seeing nothing of the enemy but "the smoke of their guns" (20 January), and concludes that "Battles are fought, not as they are planned to be, but the best way they can be." "You ask if I was not frightened at Port Royal Ferry," he writes to Miss Leavitt on 6 March 1862. "Candidly, no," he responds, "Indeed I think scarcely any of our regiment were." Officers often testified that in the midst of battle, they could be so entirely occupied with their responsibilities toward their men as to become oblivious to personal danger. Writing from Morris Island more than sixteen months later (13 July 1863), Edwards claims that when "sitting still and being shelled" he is able to "look on rather indifferantly," but the "sharp ping, ping, of rifle balls passing close to you is decidedly disagreeable where continuously kept up." Perhaps more unexpected for Edwards than the sights and sounds of combat was the freedom he and fellow soldiers enjoyed, while encamped on Hilton Head Island in January 1862, to rummage through abandoned homes in nearby Beaufort. "It was sad too to think of so many pleasant homes being desolated," he writes to Mary on 6 January, "but as there was no use in reflecting on that phase of the question we busied ourselves in searching for mementoes, playing patriotic airs on the secesh pianos, stuffing our pockets with books and gathering bouquets." To his amusement, among his Beaufort trophies is a copy of A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections by Jonathan Edwards (his great-great-grandfather), which he offers to send to Mary if she will read it. Following Port Royal, Robert spent several weeks picketing on and near Daufuskie Island, South Carolina, while the 48th assisted in the construction of batteries to prevent the resupply of Fort Pulaski. Following the fort's capture, he spent the time there in relative ease, with the monotony of garrison duty interrupted by occasional foraging expeditions, a bout of illness, and in August 1862, a "young hurricane" (3 September 1862). Frustrated by news of successive Union defeats in Virginia, Robert frequently laments his inability to contribute more directly to the war effort. "If no move is soon made I shall try hard to get into the Army of the Potomac," he writes on 5 October 1862, "I am tired of this holiday soldiering." By Christmas 1862, as he writes in the aftermath of the Union defeat at Fredericksburg, he is "almost in despair of the war's ever coming to a successful issue." He speaks again of seeking a transfer to the Army of the Potomac, though he confesses having "no desire to have a share in such a slaughter as that of Fredericksburg." Although testimony from friends and acquaintances depicts him as a committed evangelical Christian, his letters reveal little concern with proselytizing or dogma, and do not suggest that his religious faith alone defined his views on the war or on his duties as a soldier. He does complain on 2 March 1862 that his duties prevent him and his men from observing the Sabbath regularly, and writes that "prayer meetings have languished from having no place to hold them in except our tents." Despondent over the limited progress of the war, he writes on 25 December 1862, in a letter to Miss Leavitt, that "We must trust in God 'though he slay us,'" but he confesses that he is unable "to find much Consolation in the idea that our overthrow as a nation will in the end be for the benefit of the world. Resignation is all that we owe I suppose." He is especially convinced of the civilizing influences of education, and writes in a 2 March 1862 letter to Charley that despite the disadvantages of camp life, the presence in the regiment of a "large sprinkling of educated intelligent men" has had a beneficial effect on the men from lower socio-economic strata. Perhaps as exceptions to the rule in Civil War field armies, Edwards mentions members of "Perry's Saints" who managed to give up alcohol after prewar careers as "confirmed drunkards." The years 1862-63 were especially good ones for Peele, Hubbell, & Co., whose joint account with the other American trading firm in the region, Russell, Sturgis, & Co., controlled fully a third of the world's supply of hemp (Owen, "Americans in the Abaca Trade," 203). Between 1856 and 1870, business was prosperous by and large, but the Philippines export trade was volatile and the firm operated at razor-thin margins, with large profits often negated by equally large losses. In his letters, Ogden often writes of "that good time acoming" (17 May 1863) when he and his family could leave the Philippines for good. They did return to the U.S. in 1866, but economic downturns forced Ogden to return periodically to Manila until 1887, when Peele, Hubbell, & Co. finally went into bankruptcy (Owen, "Americans in the Abaca Trade," 207). Ogden, nine years Robert's senior, frequently addresses Robert in a fatherly tone, offering his younger brother advice and reassuring him that he has chosen the proper course of action. Upon hearing of Robert's joining the army, Ogden tells his brother on 1 November 1861 that he is "in the path of duty—I think I have never loved you so much as now. Not even when as a little totling thing I hushed you to sleep in my arms, or tended and assuaged your childish griefs." Judging from these letters, neither man seems to have been a particularly staunch unionist at the outset of the war. Underlying Robert's decision to enlist and his older brother's support for that decision, more than moral conviction or political ideology, is a sense of duty and a desire to restore the country's affronted honor. On 8 November, Ogden writes that "whether this rebellion is crushed or not, whether the Union is restored or a separation agreed to," Robert's fulfillment of his duty—to nation and to class—is paramount: Let this be your constant aim to do your duty well in the station in which you happen to be, at the same time that you are fitting yourself to perform duties of a wider range — You know the French proverb "noblesse oblige" — the men of our race have their obligations to the stock from which they spring—and you are not one to forget them. In 1861, neither Ogden nor Robert seems to have had especially strong feelings on the issue of slavery. By the spring of 1862 Robert accepted that emancipation would be a likely outcome of a Union victory—indeed, he dreads the prospect that "some miserable temporary Compromise" on slavery might halt the war prematurely and reinstate the volatile pre-war status quo. Yet in these letters he does not express a clear moral opposition to slavery, nor does he entertain the prospect of full and equal citizenship for freed slaves. Instead, he writes in favor of expatriation. "It is hard to turn the poor fellows out of the Country," he admits to Charley on 20 April 1862, "but I wish with all my heart they were all in Hayti or most anywheres else except these United States." Proposals to deport freed blacks to prospective colonies in Africa or the Caribbean had significant support in the North at the time, with advocates including President Lincoln, and they led to intense debate among black and white Northerners alike about the nature and extent of African American citizenship. Calls for a policy of emigration were fueled by general prejudice, of course, and by fears of a massive influx of Southern blacks who would compete with poor whites for unskilled labor. Robert, however, was convinced that Southern blacks would pose no such threat, writing that the "Contrabands" he had seen in South Carolina were "neither so industrious or intelligent of course as our poor whites at the North." Yet he sympathizes with Southern whites' overriding fear that the abolition of slavery would upset the South's traditional racial hierarchy and blur boundaries between former master and former slave, citing a "deteriation of race" as an inevitable effect of emancipation in the South. Over the course of the war, Ogden became increasingly convinced of the moral as well as political expediency of emancipation. In a letter to Robert of 7 December 1862, he welcomes news of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation Lincoln issued on 24 September, following the Union victory at Antietam. On 7 August 1863, he writes that the "war has changed me from a negative Anti Slavery man to an earnest advocate of immediate Emancipation," and he speculates that McClellan's disastrous failure on the Peninsula is divinely-authored penance for the great national sin. On the related question of how to best employ freed blacks to further the Union cause, Ogden consistently supports the enlistment and arming of black troops. On 9 May 1862, Maj. Gen. David Hunter, commander of the Military Department of the South, issued a proclamation freeing all slaves held in the Southern states under his jurisdiction (see Official Records, Series 1, vol. 14, p. 341). Ogden writes on 24 July 1862 of his surprise at Hunter's proclamation, noting its political awkwardness and inconsistency with the Lincoln administration's stated policies. Indeed Lincoln, fearing negative reaction in the border-states, had rescinded Hunter's order ten days later, but by mid-summer 1862 the president was ready to make emancipation a Union war aim, and to use black enlistment as a means to that end. Beginning on 17 August 1862, Ogden repeatedly advises Robert to consider taking a commission in one of the black regiments, supposing this to be the quickest way for Robert to advance in the army. As Ogden writes on 14 September 1862, If you want to follow the military line of life get the command of a company in one of those now despised Regiments – There is no reason why blacks in America should not make as good troops as in the West Indias. They are better material than the Sepoy regiments of British India, the Indigenes (French) of Cochin China, or the Japals employed here by the Spaniards – Each & all of which when well led make good troops. Robert certainly fits the profile of the white officers—mostly educated New Englanders and New Yorkers of the middle and upper classes—who accepted commissions in the black regiments authorized for Union service beginning in the fall of 1862. But he seems not to have been convinced of their potential for combat service, and in this he reflects the opinion held by the majority of white Northerners. Robert writes on 20 April 1862, after limited experience with freed slaves on the Carolina coast, that it is "of no use to talk of arming them. I have not yet seen one whom I would trust. There is no fight in them as a class." It appears that he moderated his views somewhat—Ogden comments in a letter of 4 January 1863 on Robert's "idea" of attaching two black companies to each white regiment, provided that the black troops would be subject to stricter discipline and used in non-combat roles—but his letters provide no evidence that he ever seriously weighed taking a commission in a black regiment. His motives for not doing so were perhaps several, yet Ogden writes to Robert on 7 August 1863 that he regrets his brother's "prejudice against colored troops as otherwise you could probably have obtained a command in Genl Banks 'Corps d'Afrique.'" Though he was reluctant to fight alongside black troops, Robert did employ a young contraband valet known as "Careless" during his time on the coastal islands (letter of 1 January 1864). Careless apparently remained with Robert as the 48th took position for the 18 July assault on Fort Wagner, and lingered on the beach, "in great danger of being cut to pieces from shells," to await his employer's return.

Extent

.46 Cubic Feet : 62 folders

Language of Materials

English

Abstract

Around 60 items, mostly manuscripts, with a bearing on the Civil War service of Lt. Robert S. Edwards of the 48th New York Infantry. Among the 45 personal letters are 14 written by Edwards and 22 directed to him by his brother and sister-in-law, Ogden and Nellie Edwards, then living in the Philippines. There are also a number of items relating to Robert Edwards's death (at Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor) and post-mortem arrangements.

Arrangement

Materials are arranged chronologically, one item per folder

Subject

- United States. Army. New York Infantry Regiment, 48th (Organization)

Genre / Form

Geographic

- Title

- Robert S. Edwards Papers

- Status

- Completed

- Author

- George Rugg

- Date

- 2012

- Description rules

- Describing Archives: A Content Standard

- Language of description

- English

- Script of description

- Latin

- Language of description note

- English

Repository Details

Part of the University of Notre Dame Rare Books & Special Collections Repository